Newsletter

Medical Perspective: Benefits and Risks of Using Guidelines

Apr 01, 2010

At the CRICO/RMF Strategies patient safety conference in June 2009, the audience of clinicians and other patient safety leaders got to see something very unusual. They saw a health care expert stand up and advocate for a patient safety intervention—and then they watched a top Boston malpractice defense attorney pick it apart. They saw the benefits, and then heard the risks…in real time…from people with specialized knowledge about benefits and risks. The attorney did not say “don’t do it,” just be aware of the liability pitfalls—and prepare for them.

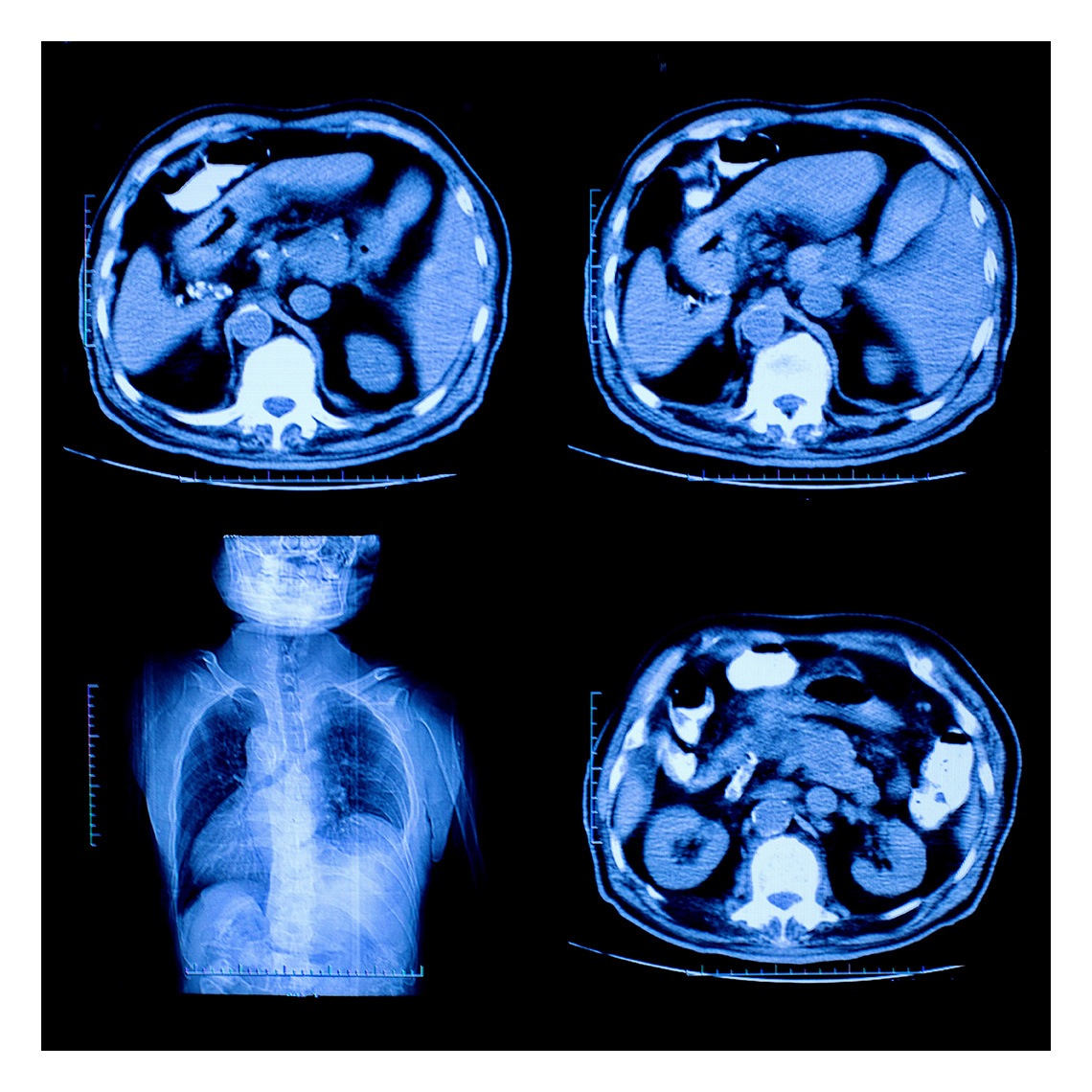

First, Dr. Mark Graber, Chief of the Medical Service at the VA Medical Center in Northport, New York, argued that the literature is rife with experiments showing variability among clinicians diagnosing the exact same clinical scenarios, such as radiologists interpreting films or physicians interpreting symptoms that could be two different diseases.

“Variability in clinical performance is a critical factor that detracts from quality and safety,” said Graber. “Is there anything we can do about this? I think there is, and it’s pretty simple. The solution is wider and more consistent use of clinical guidelines and algorithms.

“Many clinical studies have shown that rules based on actuarial judgment usually work better than individual clinical judgment. Actuarial judgment is really the norm throughout industry. That’s how people decide whether we should get our health insurance policy, what we should pay for it, whether we should get a loan, whether somebody should be paroled. It’s achieved unanimous acceptance—mostly outside of medicine, I’m sad to say.”

Graber went on, “So, why don’t we use these more? Are there any examples in medicine? Well, there certainly are.

“Goldman was troubled by the question of people coming to the emergency room with chest pain. How do you know the best thing to do?

“Goldman studied 10,000 cases to see who had complications in the next day or two. There were 40-50 different parameters that were examined; however, he came up with a rule that used only four. Those four parameters predicted with substantial accuracy how well somebody was going to do:

-

Are you having an MI or are there signs of ischemia?

-

Is your blood pressure less than 110?

-

Do you have rales in your lung?

-

Do you have a past history of MI?

"That’s it, four parameters, and on the basis of those, he could divide people very effectively.

"People in the lowest risk group had complications 0.2% of the time in the next couple of days. People in the highest quartile had problems 25% of the time.”

Graber pointed out that Goldman’s theory was tested very effectively at Cook County Hospital where they looked at case scenarios and they looked at real patients to see how well the Goldman rule would do. They did a pre- and post- type of study and the rule worked extremely well.

- The rate of missing a patient who had a complicated MI dropped from 11% to 6%—a big, big drop.

- Also, the number of patients who were inappropriately admitted to an ICU who didn’t actually need that level of care was reduced from 38% to 27%.

“So these rules work,” Graber concluded.

“They work outside of medicine and they work inside of medicine. They work in theory and they work in practice, and I’d like to propose that if we could only use these rules, we’d have more quality and more safety in medicine today.”

This page is an excerpt of a full issue of Insight.

CME: The Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine has endorsed each complete issue of Insights or 30-minutes of podcast episodes as suitable for 0.5 hours of Risk Management Category 1 Study in Massachusetts. You should keep track of these credits the same way you track your Category 2 credits.Recent Issues

Who’s Who in Health Care?

A First Place Mindset About Medical Error

Utilization of Electronic Health Record Sex and Gender Demographic Fields: A Metadata and Mixed Methods Analysis

Establishing a Regional Registry for Neonatal Encephalopathy: Impact on Identification of Gaps in Practice