Newsletter

The Diagnostic Multiverse

Mar 28, 2023

The movie that recently won seven Academy Awards, Everything, Everywhere, All at Once capitalized on the concept of a multiverse, in which several versions of the same physical universe coexisted. It is not a new idea; this phenomenon has been well-explored by the likes of Robert Heinlein, Philip Pullman, Stephen King, and Dr. Who.

Fundamentally, a multiverse is based on “what ifs.” What if this person had lived instead of died? What if apes were the dominant primate? What if our fingers looked like hot dogs? The options are endless and creating them on paper and on film is great fun.

In a less entertaining way, medicine has its version of the multiverse, known as the differential diagnosis. For any patient with signs and symptoms and test results that don’t fully confirm a precise diagnosis, creating a differential diagnosis is considered best practice. By taking into account the possible diagnoses that share symptoms present for a given patient, current and future providers are then able to rule out secondary options via testing and observation.

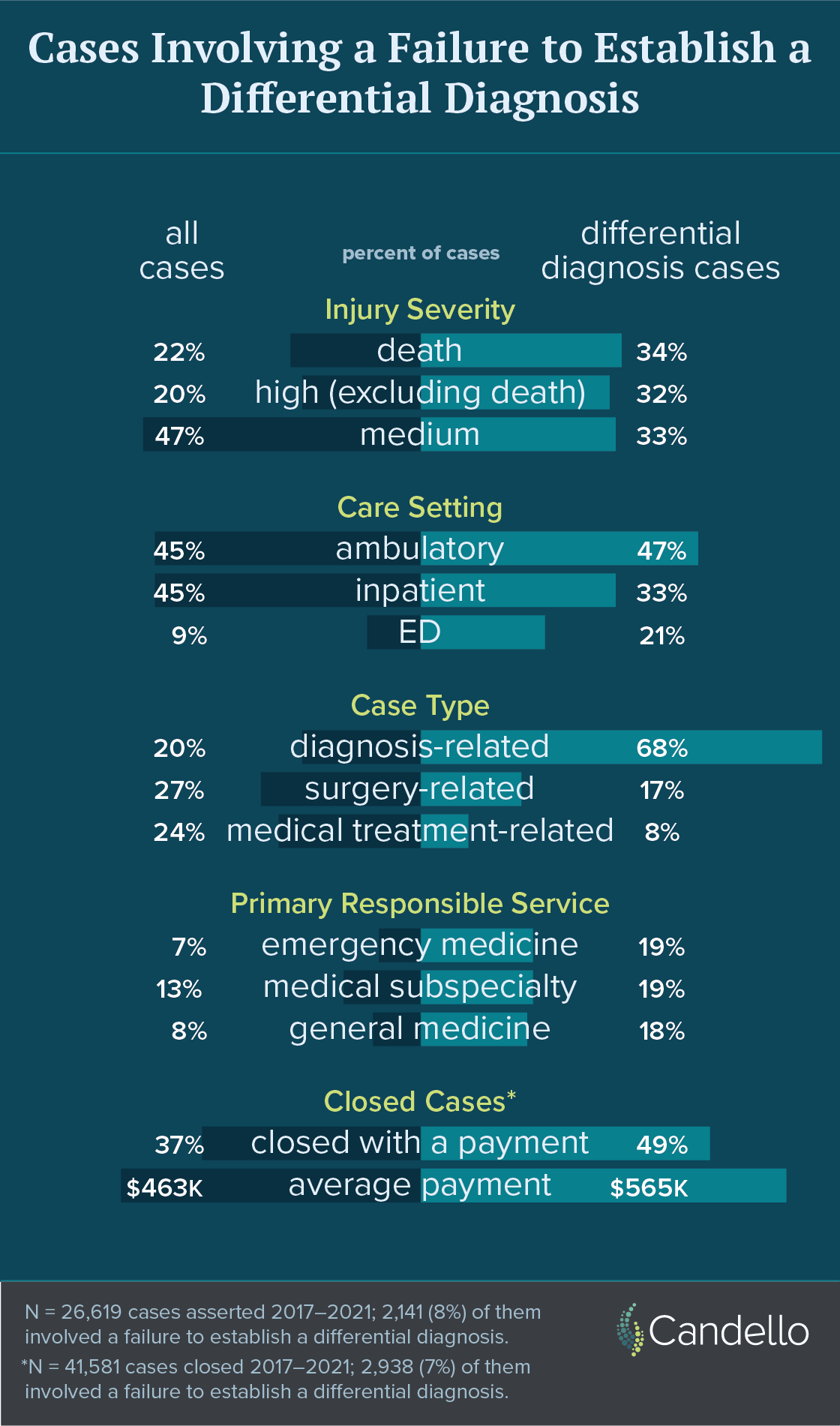

When that step of establishing and investigating a differential diagnosis is not taken—and a narrow diagnostic focus delays the correct finding—the patients may suffer irrevocable harm and the clinicians involved may be accused of medical negligence. Based on Candello data, an analysis of more than 26,000 medical professional liability cases asserted from 2017 to 2021 indicates that eight percent cited the failure to establish a differential diagnosis as a contributing factor.

Unsurprisingly, two-thirds of the differential diagnosis cases alleged a missed or delayed diagnosis, with another 25% involving surgery or medical treatment issues. The injury severity in such cases is notably greater than for MPL cases overall, with two-thirds involving a significant and permanent injury, or death. Three areas of service share the brunt of these cases, with Emergency Medicine involved in almost one-fifth.

Accepting uncertainty—and communicating that to patients—is the foundation for avoiding this type of misstep and keeping your patient safe. Among his prolific research in the realm of diagnostic error, Dr. Gordy Schiff has extensively studied diagnostic pitfalls, including the area of narrow diagnostic focus that is often behind the failure to establish and investigate differential diagnoses.1

One of Schiff’s key takeaways is a set of questions clinicians who have accepted uncertainty should consider as they continue the diagnostic process.

-

What else might this be? This is a way to force oneself to make a differential diagnosis.

-

What doesn’t fit? Make sure unexplained abnormal findings are not dismissed.

-

What critical diagnoses are important not to miss?

-

Do we have reliable “closed loop” systems, i.e., for following up, labs, imaging, referrals, etc.?

-

Does the safety culture in our office support blame-free sharing of errors and questioning another clinician’s diagnosis?

-

How does our electronic health record help (or hinder) establishment and pursuit of differential diagnoses?

Documentation, e.g., creating a differential and closing the loop on potential diagnoses in the context of uncertainty, is critical for both future caregivers and in the defense of an allegation that a missed diagnosis was complicated by a failure to explore a similar, but different, reality.

1Characteristics of disease-specific and generic diagnostic pitfalls: a qualitative study

Additional Materials

- How to tell patients you’re not sure

- Differential diagnosis: the key to reducing diagnosis error, measuring diagnosis and a mechanism to reduce healthcare costs

- Teaching heuristics and mnemonics to improve generation of differential diagnoses

- Five strategies for clinicians to advance diagnostic excellence

- MultiVerse: Causal Reasoning using Importance Sampling in Probabilistic Programming

Recent Issues

Getting to the Detail Devils

An MPL Perspective on the SafeCare Study