Article

MIMESPS: Learning from Malpractice Cases

Funding and Participants

The Malpractice Insurers’ Medical Error Surveillance and Prevention Study (MIMESPS) was funded by CRICO and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality(AHRQ).

Five malpractice insurance companies based in four regions (Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, Southwest, and West) participated in the MIMESPS study, granting access to their claim files for purposes of clinical review. The insurers included, CRICO (Harvard-affiliated hospitals), MCIC Vermont (Yale, Johns Hopkins, U. of Rochester, Columbia Presbyterian OB only), University of Texas Healthcare System (Hermann Hospital, San Antonio, Galveston), Kaiser Permanente (Southern California region) and Lifespan (Rhode Island, Newport and Marion Hospitals). Collectively, they covered approximately 33,000 physicians, 61 acute care hospitals (35 academic and 26 nonacademic), and 428 outpatient facilities. The study was approved by ethics review boards at the investigators’ institutions and each review site.

Project Purpose

MIMESPS had five broad aims:

- To harness the potential of professional liability insurance programs to operate as a nationwide error reporting system through structured human factors analysis of a large number of incidents leading to malpractice claims.

- To use this approach to identify the most frequent factors contributing to error in four major categories of care (obstetrics, surgery, diagnosis, medication administration) as well as in specific problems areas (e.g., retained foreign bodies after surgery, fetal injury during prolonged second stage of labor).

- To test case-control analysis as a method of quantifying the role of various contributing factors (alone and in combination) to the occurrence of specific errors.

- To assess how the errors and contributing factors identified in claims file analysis compare to those identified through other types of reporting systems.

- To design, disseminate, and implement a series of targeted patient safety interventions based on results from the contributing factor analyses.

Study Design

The study consisted of a review of claim files at participating insurers by physicians trained to use a sequence of instruments. The instruments were designed to:

- detect injuries due to medical care (as opposed to the underlying disease process);

- guide implicit judgments as to whether those injuries were due to treatment or diagnostic error;

- disentangle the etiology of errors identified.

Data Sources: The Claim File Sample

Data were extracted from random samples of closed claim files at each insurer. The claim file is the repository of information accumulated by the insurer during the life of a claim. It captures a wide variety of data, including the statement of claim, depositions, interrogatories, and other litigation documents; reports of internal investigations; expert opinions from both sides; medical reports and records detailing the plaintiff’s pre- and post-event condition; and, while the claim is open, medical records pertaining to the episode of care at issue. We reacquired the relevant medical records from insured institutions for sampled claims.

Following previous studies, we defined a claim as a written demand for compensation for medical

injury.[ i, ii] Anticipated claims or queries that fell short of actual demands did not qualify. We focused on four clinical categories and applied a uniform definition of each across insurers: (1) obstetric; (2) surgical; (3) missed and delayed diagnoses; and (4) medication. Alleged injuries in these categories dominate the caseload of malpractice insurers in the United States, accounting for approximately 80% of all claims and an even larger proportion of total indemnity costs.[iii,iv,v]

Insurers contributed to the study sample in proportion to their annual claims volume. The number of claims by site varied from 84 to 662 (median=294). One site contributed obstetric claims only; another site had claims in all clinical categories except obstetrics; and the remaining three sites contributed claims from all four clinical categories.

Data Collection: The Claim File Review

The reviews were conducted at the insurers’ offices or insured facilities by physicians who were board-certified attendings, fellows, or final-year residents in surgery (surgical claims), obstetrics (obstetric claims), and internal medicine (diagnosis and medication claims). Physician investigators from the relevant specialties trained the reviewers in the content of claims files, use of the study instruments, and confidentiality procedures in one-day sessions at each site. The reviewers were also assisted by a detailed manual. Reviews took 1.6 hours per file on average and were conducted by one reviewer. To test the reliability of the review process, 10% of the files were re-reviewed by a second reviewer who was unaware of the first review.

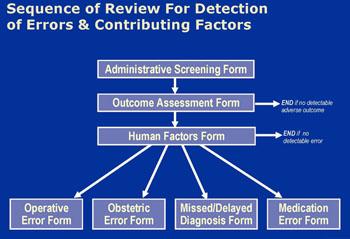

Reviews followed a sequence of 4 instruments (Figure 1). For all claims, insurance staff recorded administrative details of the case and clinical reviewers recorded details of the adverse outcome the patient experienced, if any. Physician reviewers then scored adverse outcomes on a 9-point severity scale ranging from emotional injury only to death.[vi] Review terminated for claims without identifiable adverse outcomes (i.e. no score on the scale). For the rest, reviewers considered the potential contributory role of 17 “human factors” in causing the adverse outcome. These factors were selected based on a review of the patient safety literature and covered system-, clinician-, and patient-related causes.

Next, reviewers judged, in light of all available information and their decisions about contributing factors, whether the adverse outcome was due to medical error. We used the Institute of Medicine’s definition of error: “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (i.e. error of execution) or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (i.e. error of planning)”.[vii] Reviewers recorded their judgment on a 6-point confidence scale ranging from “1. Little or no evidence that adverse outcome resulted from error/errors” to “6. Virtually certain evidence that adverse outcome resulted from error/errors.” Claims that scored 4 (“More likely than not that adverse outcome resulted from error/errors; more than 50-50 but a close call”) or higher were classified as having an error. For these claims, reviewers completed a final form which gathered additional clinical information about the nature and circumstances of the error.

Reviewers were not blinded to the litigation outcome but were instructed to ignore it and exercise independent clinical judgment in rendering determinations about injury and error. Training sessions stressed both that the study definition of error is not necessarily synonymous with the legal definition of negligence and that a mix of factors extrinsic to merit influence whether claims are paid during litigation.

Results

Overview of Principal Findings

We reviewed 1452 claims. The breakdown of these claims by clinical category is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Reviewed claims by clinical category

| Clinical category | n | % |

| Operative | 444 | 31 |

| Obstetric | 335 | 23 |

| Missed/delayed diagnosis | 429 | 30 |

| Medication | 244 | 17 |

| Total | 1452 | 100 |

The dates of closure for the claims spanned twenty years, however most were relatively recent (Table 3). Eighty-three percent of the claims closed between 1995 and 2004; 62% closed in 1998 or later. The average time between occurrence of the injury and closure of the claim was five years.

Table 3. Time periods within which reviewed claims were closed

| Closure period | n | % |

| 1984 – 1989 | 57 | 4% |

| 1990 – 1994 | 190 | 13% |

| 1995 – 1999 | 542 | 37% |

| 2000 - 2004 | 663 | 46% |

In 3% of claims no adverse outcome from medical care was evident (Table 4). An additional 4% of claims involved emotional injury or failure to obtain the patient’s informed consent to treatment but no physical injury. The remaining 93% of claims involved physical injury, and typically these injuries were severe. Eighty percent of claims involved injuries that caused significant (39%) or major (15%) disability or death (26%).

| No injury | 3% |

| Breach of informed consent (only) | 1% |

| Psychological / emotional | 4% |

| Minor physical | 13% |

| Significant physical | 39% |

| Major / grave physical | 15% |

| Death | 26% |

Beyond these basic descriptive statistics of the study dataset, results for the project are difficult to bring together in summary form because the MIMESPS analyses are wide-ranging in nature. They are depicted

in Figure 2.

The analyses can be divided into four groups:

Group 1 consists of general descriptive papers with report results from each of the four clinical categories.

Group 2 involves sub-analyses directed at recognized patient safety problems. In some cases (e.g. missed breast cancer, wrong site surgery) these sub-analyses involve use of data drawn from within one of the four clinical categories; in other cases (e.g. analysis of residents' involvement in errors) the sub-analysis is cross-cutting and does not observe the boundaries of clinical categories.

Group 3 consists of case-control studies in which the MIMESPS data furnishes the cases and the controls come from other sources.

Group 4 involves three legal analyses which address:

- the prevalence and cost of claims that did not involve error

- claims alleging a breach of informed consent

- an etiologic analysis of the legal concept of negligence in which the litigation outcomes are compared with human factors data

Discussion & Conclusions

As with the results from this study, a brief overarching summary of conclusions is difficult; they tended to be quite specific to the analyses in question. However, several broad themes are evident:

- Value of malpractice claims in patient safety research. From a methodological perspective, we found that closed malpractice claims yielded a rich source of data about errors and the factors that caused them. The most valuable validation of this conclusion was our ability to analyze the MIMESPS data in key areas of concern in patient safety (see Figure 2, above), with results that will inform ongoing and future error-reduction initiatives. Another validation came in the form of a question posed to reviewers toward the end of the Human Factors Form. Reviewers were asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale the value the medical record and other information in the claims file, respectively. Table 5 summarizes the results. Although medical record review remains the gold standard in large scale retrospective review of medical injuries, we believe that claim file review, represents an improvement on this methodology in some key respects.

- Cognitive and system errors. We found that systems factors played a critical role in the occurrence of errors. Individual errors in judgment, vigilance, or memory were certainly not irrelevant.

On the contrary, approximately nine out of ten errors involved at least one of these cognitive factors. More than three-quarters of the time, however, they acted in concert with other more system-oriented factors (e.g. communication breakdowns, supervision problems) in producing harm. This was true even among those surgical errors which, at a superficial level, appeared to be purely technical in nature. Patients’ role in errors. Patient-related factors, both behavioral (e.g. compliance, follow-up) and clinical (e.g. difficult anatomy, atypical presentation) were also critical contributors to errors. They were present in approximately one third of all errors detected in MIMESPS. - Multifactorial nature of errors. Our findings highlight the complexity of errors, especially diagnostic errors that occur in the ambulatory care setting. Just as Reason’s “Swiss cheese” model of accident causation suggests,[viii] diagnostic errors that reach patients appear to result from the alignment of multiple breakdowns, which in turn stem from a confluence of contributing factors. For example, the median number of contributing factors involved in diagnostic errors in the outpatient setting was 3; 59% had >3 contributing factors, 27% had >4, and 13% had >5.

- Trainee involvement in errors. Trainees were involved in approximately one third of errors detected in our study. To some extent this reflects MIMESPS’ focus on teaching hospital settings. Nevertheless, supervision breakdowns and lack of experience emerged as important human factors, and these breakdowns were driven largely by the involvement of residents, fellows, and interns.

- Frivolous litigation. Findings from out litigation analyses suggested that frivolous litigation may not be as large a problem as some in the recent debates over medical malpractice reform have suggested. Although a non-trivial proportion of claims lack evidence of error, their fiscal impact tends to be limited because the system performs quite well in denying them compensation. The vast majority of resources go toward resolving and paying claims with errors.

Implications

In many respects, the findings to date from the MIMESPS project are humbling. They shed light on the tremendous causal complexity that underlie many errors. The task of effecting meaningful improvements to the medical care process—with its numerous clinical steps, stretched across multiple providers and months or years, and the heavy reliance on patient initiative—looms as a formidable challenge. The prospects for “silver bullets” in this area appear remote. Our results underscore the need for continuing efforts to develop the “basic science” of error prevention in medicine[ix]which remains in its infancy.

However, the public demands action today. Are meaningful gains achievable in the short to medium term? The answer will likely turn on whether relatively simple interventions that target two or three critical breakdown points are sufficient to disrupt the causal chain, or whether interventions at a wider range of points is necessary to avert harm. An important goal of the MIMESPS research was identify key points of breakdown and link them with interventions that have the potential to attenuate them.

References

- Weiler PC, Hiatt HH, Newhouse JP, Johnson WG, Brennan T, Leape LL.A measure of malpractice: medical injury, malpractice litigation, and patient compensation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Studdert DM, Brennan TA, Thomas EJ. Beyond dead reckoning: measures of medical injury burden, malpractice litigation, and alternative compensation models from Utah and Colorado.Indiana Law Rev.2000;33:1643-1686.

- Physician Insurers Association of America. Data sharing report (2000).

- Chandra A, Nundy S, Seabury SA.The growth of physician medical malpractice payments: evidence from the National Practitioner Data Bank.Health Aff.2005; May 31. (e-print)

- National Practitioner Data Bank. Public Use Data Files (http://www.npdb-hipdb.com/publicdata.html. Last accessed September 27, 2005.)

- Sowka M, ed. National Association of Insurance Commissioners, malpractice claims: final compilation. Brookfield, WI: National Association of Insurance Commissioners, 1980.

- Corrigan J, Donaldson M, eds. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2000.

- Reason J.Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 1997.

- Brennan TA, Gawande AA, Thomas EJ, Studdert DM. Accidental deaths, saved lives, and improved quality.N Engl J Med.2005;353:1405-1409.

Related Articles

Are Attendings Liable for Residents’ Negligence?

Is the attending physician for an inpatient legally responsible for all the care provided by the clinical team while a patient is in the hospital? The short answer to this question is: No.

The Physician’s Legal Duty to Non-Patients